Review: Sing Sing (2023)

Based on the plot description and the rave reviews of easily-baitable critics, it’s easy to assume that Sing Sing is a cloyingly inspirational feature, one that uses its “based on a true story” narrative, prison setting, and blend of real life and fiction to tug at the heartstrings of a viewer who is primed for any message that combines art with social justice. We’re lucky, then, that Sing Sing is only occasionally the film it could so easily be throughout. Mostly, Sing Sing is a performance showcase, as in, a showcase for the professional actor Colman Domingo and the real men of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program at Sing Sing Maximum Security Prison. But it’s also a showcase of performance and the theatrical process of learning to act. In its best moments, it plays like a fly-on-the-wall documentary about the acting process and about how to transform tense non-professional performers into confident actors.

Based on the real RTA program at the infamous prison, and incorporating many of the program’s members (past and present) into the cast, Sing Sing is part documentary, part inspirational drama. It’s much more successful as the former than the later, as screenwriters Clint Bentley and Greg Kwedar (who also directs), let a few too many of the typical beats of the inspirational drama creep into the narrative. The music by Bryce Dessner doesn’t help either, with its tear-jerking swells. Luckily, these remain smaller features of the film, but they do sneak their way into how the film handles Colman Domingo as Divine G, the central figure of the RTA who writes plays in prison and is the most accomplished and confident actor of the bunch.

For instance, Bentley and Kwedar write the film so that Divine G. is in prison for a crime he didn’t commit (I’m reminded of the old joke that everyone in prison is innocent) and his appeals for clemency and his “trust in the process” go unrewarded. These aspects are understandable yet unnecessary. We don’t need to believe that Divine G. is innocent to be invested in him, a fact proven by all the other characters, who are admitted criminals yet charismatic and sympathetic in their own rights. Furthermore, the most genuinely fascinating moments of Sing Sing are about the process of performance itself: how to rehearse, how to make the role your own, how to process your emotions and connect with the audience through a performance. A character’s innocence doesn’t really affect their performative process. At the same time, the less the movie tries to cater its performances to the viewer, the better it plays.

The plot, such as it is, focuses on the RTA as they embark on a new production. The newest member of the group, a prison yard tough known as Divine Eye (played by himself), thinks they should do a comedy and so all the members of the group throw out ideas of what it should be about. No one can agree on anything, so the program director, Brent (played by the exceptional Paul Raci from Sound of Metal), decides to write an original work that incorporates all the elements raised. The result is Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code, which blends ancient Egypt, Robin Hood, Freddy Krueger, and Hamlet into a spoofish piece that is familiar to anyone who’s ever attended a dinner theatre. And placed in the role of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who seems dumped into this farce, is not Divine G., but Divine Eye. Thus, the film is about this initial conflict between the two Divines, but grows into an examination of their relationship and their approach to acting. In the process, it becomes a movie about rehearsal and performance, what we tell ourselves and what we show others, and about a possible path to healing.

Much of the runtime follows the rehearsal process. We watch Brent talk about how to perform, and more importantly, we see the inmates put through exercises that loosen them up and help them be more authentic and spontaneous on stage. We also get some riveting moments of introspection and directorial challenges that add specificity to these moments. These scenes of rehearsal go on longer than would be allowed in a typical film, but because the movie is mostly about people playing themselves, Kwedar and company give the men the room to try things out and stay in the moment. You start to wonder whether the movie itself was a therapeutic exercise for these men, many of whom are inmates in real life, and thus, another extension of the RTA program’s mission statement.

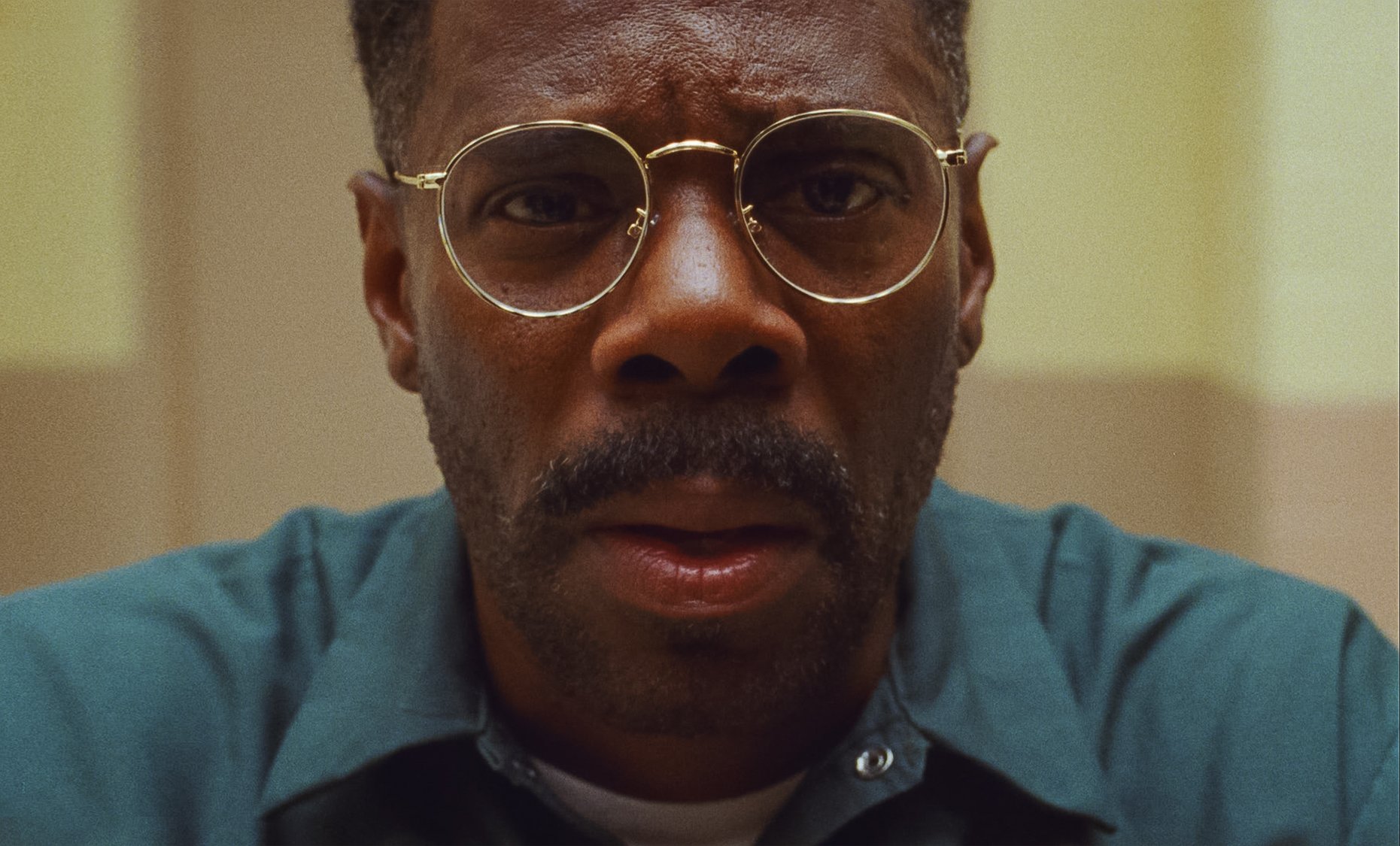

At least, this applies to all the men but Raci and Domingo. Much as he was in Sound of Metal, Raci is great here, projecting the kind of warmth and intelligence and sensitivity that is perfect for the role of the quiet director. As for Colman Domingo, he’s almost too good for Sing Sing. Not too good for the film, which is certainly good in its own right, but almost too good a performer to exist on the wavelength of the other performers, such that you sometimes cannot help but notice that this acclaimed thespian is performing alongside a bunch of non-professionals who are playing parts inspired by their own lives.

The non-professionals themselves are a real pleasure to watch. Much of the joy of watching non-professionals in a movie is to be surprised by the lack of guile and showiness that comes so naturally to the rich and famous. Non-professional actors might not be able to massage a line-reading like a pro, but they often have an uncanny ability to let us see their essence through the performance and to surprise us with the earnest approach to a line or a moment. Sing Sing demonstrates this throughout.

But Domingo stands out as the only professional Hollywood star of the group. However good an actor he is, he is so convincing and accomplished with his line readings and reactions that we sometimes question his performance in relation to the others. It’s not that he refuses to play down to those around him—that would be an insult to the other performers, notably Divine Eye, who are very good. It’s that we wonder whether Domingo, as Divine G, is being authentic. Perhaps this is intentional as Divine G seems to think he’s a different kind of person than he is; he’s falsely humble and fails to hide his pride at being the unofficial leader at the RTA. The filmmakers seem to pick up on this dynamic in the performer at times, which is why Domingo’s most authentic moments are when Divine G is giving acting advice to others or imparting some wisdom, which allows Domingo to share his own professionalism with the other performers. In these scenes, we witness a true pro sharing his tips with others and connecting with them without pretending to be the same type of performer as them.

In short, Domingo gives a good performance, but is it the right one for the film? Or is he simply held back by the fact that all the more conventional elements of the movie involve his character? Because he’s not playing a version of himself, unlike most of the supporting cast members, there isn’t the same level of discovery that accompanies watching non-professionals tackling such a surprising work. Regardless of the answer, Sing Sing still works, sometimes in spite of itself. It’s an ode to acting, first and foremost. It’s not seamless or without its dramatic inconsistencies, but at its best, it’s an insightful and authentic look at the therapeutic and redemptive power of art.

7 out of 10

Sing Sing (2023, USA)

Directed by Greg Kwedar; written by Clint Bentley and Greg Kwedar, based on a story by Clint Bentley, Greg Kwedar, Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, and John “Divine G” Whitfield, “The Sing Sing Follies” by John H. Richardson and Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code by Brent Buell; starring Colman Domingo, Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin; Sean San Jose, Paul Raci, David “Dap” Giraudy, Patrick “Preme” Griffin, Jon-Adrian “JJ” Velazquez, Sean “Dino” Johnson.

Jurassic World: Rebirth recognizes the core appeal and best aspects of previous Jurassic movies and delivers on these in a capable manner.