Review: The Boy and the Heron (2023)

“How do you live?” This is the formative question posed by Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (and the Japanese title of the film). The Japanese master of animation returns 10 years after another false retirement and supposed swan song, The Wind Rises, with a film that, at first glance, looks like a grab bag of Miyazaki storytelling obsessions. A 12-year-old boy, Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki), staying in the country with his father (Takuya Kimura) and his new wife, who happens to be his aunt (Yoshino Kimura), enters a magical world to rescue this new step-mother and prove himself a man. He has to pass through fantastical environments that shift like dreamscapes, learn lessons about the transition to adulthood and responsibility, and make a choice between staying in this dreamworld or returning to his mundane reality. Sound familiar?

The Boy and the Heron has deliberate callbacks to My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away, and the animation is also familiar, with designs and environments recalling past films, from the forest spirits of Princess Mononoke to the planes full of dead flying aces in Porco Rosso. But The Boy and the Heron is not a greatest hits for Miyazaki, nor is it a redundant story of childhood growth. This is because of this central question—“How do you live?”—which gives the film its animating spirit.

This is the question posed in the book possessed by Mahito’s late mother, which he discovers accidentally while fashioning a bow and arrow in her former study. It’s the formative question for Mahito, ultimately of how he will live in the aftermath of the death of his mother, who perished in a fire at her Tokyo hospital in the midst of World War II. Mahito is an angry boy and he spurns his new environment, his new step-mother, his new school. After fighting with some boys on the way home from classes, he deliberately bashes his own head with a rock.

The inscrutability of this action—was Mahito trying to kill himself, to sustain an injury he could blame on the other boys, to simply escape his current circumstances—is crucial, and much of the film has a similar opacity. The Boy and the Heron is not beholden to conventional logic. Characters are motivated by suppressed emotions, magical environments shift like waves on the ocean, and rules are changed and discarded throughout. The wayfinder through all the emotional and environmental turmoil is Mahito’s deeply-felt pain, his grief at his mother’s loss, and his confusion at the violence of the world he lives in.

Mahito is looking for a way out, or at least a distraction. He finds both when a grey heron arrives at the pond on his father’s property, near the munitions factory he runs. The heron torments the boy and the boy decides to kill the heron, or at least follow it into the mysterious tower that sits on the property near the pond. When his new step-mother disappears into the tower, pregnant with his incoming sibling, Mahito follows her, knowing the heron has taken her. But to where, and for what purpose?

Mahito discovers the where and the what at the same time we do, passing into a fantastic world of indescribable beauty and haunting solemnity. Inside the tower, after confronting the heron, a mysterious voice bids him search for his step-mother alongside the heron and the floor falls out from under him. He falls to a new world below, where waves stretch as far as the eye can see, and tiny boats and archipelagos pock the immense, deep blue waters. Anyone familiar with Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series, and Miyazaki’s own affection for Earthsea, will recognize the influences of Le Guin’s fantasy world, where a great ocean binds together the disparate kingdoms and magical realms of her universe. The Boy and the Heron occurs in a similar world, although one that is more akin to the realm beyond the wall in The Farthest Shore, a physical landscape in spiritual limbo. This world is tactile, but it is not physical; it’s real, but not our reality.

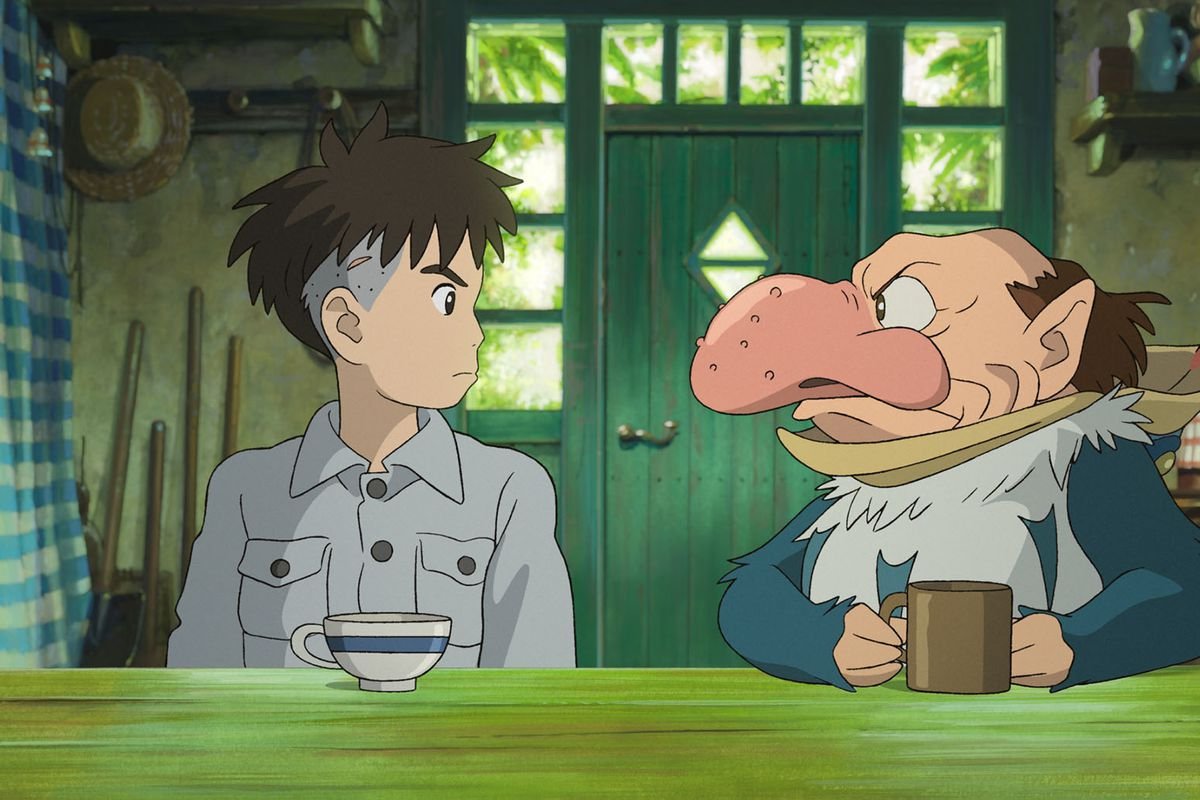

Mahito journeys through this world alongside the heron, who becomes something of a man and is voiced by the raspy, gravely Masaki Suda, in search of his step-mother. He meets figures who are familiar variations on people he knows in the real world, similar to the characterizations in The Wizard of Oz (another common Miyazaki influence, especially on Spirited Away). He fights against the bird people who have invaded this dream world, especially the parakeets who have colonized the tower that exists in this world and Mahito’s own simultaneously. He is offered immense power, faces immense evil, and endures harsh trials, which challenge his physical endurance and his moral worth.

The journey is enchanting, beguiling, the sort of adventure into the heart of dreams that showcases the imaginative possibilities of moviemaking, and Miyazaki’s own unique talent for animating the profound. But even more than most of Miyazaki’s previous films, The Boy and the Heron is not enamoured of its fantasy world. Chihiro has to go home in Spirited Away to live a real life, now equipped with new wisdom, but she is not confronted with the moral horror of her own world at every turn while exploring the spirit realm of the bathhouse. But Mahito, while very much a male counterpart to Chihiro, as angry as she is impudent, violent as she is sad, is constantly confronted with the horrors of the real world. Is it a world worth returning to? Is it not better to escape into this dreamworld and create a new reality free from war and grief?

The Boy and the Heron is most similar to Spirited Away, but it draws a key visual from Grave of the Fireflies, the heartbreaking World War II drama from Miyazaki’s late Studio Ghibli founding partner, Isao Takahata. In the film’s opening minutes, a fire engulfs the hospital where Mahito’s mother works as a nurse. He races through the Tokyo streets, ignoring the words of his father, in hopes of getting to the hospital in time to save his mother. But it’s too late, as the fire at the hospital (it’s never explained whether the fire was from a bomb or not) is too powerful.

The heat of the flames burns down the wooden building and seems to warp the film’s very frame. The animation gives way to wavy, indistinct stylization, the fire seeming to burn away clear outlines. It recalls the Princess’s flight from the castle in Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, where peeling back the animation reveals more than more detailed work ever could. The imagery is more haunting than anything we get in the dream world inside the tower, and the image of his mother consumed in flame, rising into the sky like a star, returns to Mahito frequently. It’s the horror of reality that haunts him. It’s the traumatic memory that confronts him with the question left by his mother: “how do you live?” How do you live with loss? How do you live with malice? How do you live with your dreams? Do you escape the world or try to change it? What good are the dreams we make, the stories we tell, the legacy we leave behind, in the face of the horrors of war?

In the end, Miyazaki is questioning his whole legacy, his whole work with Studio Ghibli, because he is Mahito, he is the old man at the end of his life confronting what’s next through the child that stands in for him. The Boy and the Heron is a captivating fantasy, but it’s the too true, too real question at its centre that gives it its enduring power: how do you live in the real world?

9 out of 10

The Boy and the Heron (2023, Japan)

Written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki; starring Soma Santoki, Masaki Suda, Aimyon, Yoshino Kimura, Takuya Kimura, Shōhei Hino, Ko Shibasaki, Kaoru Kobayashi, Ju n Kunimura; English dub features Luca Padovan, Robert Pattinson, Karen Fukuhara, Gemma Chan, Christian Bale, Mark Hamill, Florence Pugh, Willem Dafoe, Dave Bautista.

Mayor of Mayhem is an embarrassingly lazy recounting of the Rob Ford saga.